LINCOLN — “All the marvelous surfaces” is a phrase from the photographer Karl Blossfeldt. Those words, even more than the 45 of his images in the show, are the point of departure for “All the Marvelous Surfaces: Photography Since Karl Blossfeldt.” It runs through March 29 at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum. So do “Truthiness and the News,” another photography show, and “Peter Hutchinson: Landscapes of My Life,” which is mostly a photography show.

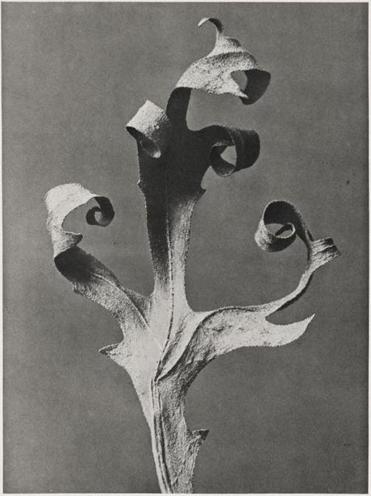

Blossfeldt (1865-1932) is famous for his plant studies: exactingly detailed, marvelously precise, organically geometric (or should that be geometrically organic?). Photographing his specimens close up, Blossfeldt was able to present them as at once exquisite and surpassingly substantial. They manage to look timeless, as if Plato’s cave has turned into a garden. Yet they’re very much of their place and time.

That place and time was Weimar Germany. Blossfeldt’s work relates to the New Objectivity, the most influential visual style at that time. As the name suggests, the New Objectivity put a premium on simplicity, directness, and the suppression of emotion. Its greatest photographic exemplar was August Sander, with his “People of the 20th Century,” a vast taxonomy of contemporary society through portraits. Blossfeldt was doing something similar, only with plants instead of people, and with nature rather than society.

No small part of the pleasure of “All the Marvelous Surfaces” is how the curators, Sarah Montross and Elizabeth Upenieks, extend Blossfeldt’s work thematically. Yes, there are some botanical studies — or simply photographs with plants in them — among the nearly 140 images on display. But with most, the relationship to Blossfeldt is conceptual, through a shared emphasis on surface, ornament, typology, or sculptural solidity. Considering how widely the show ranges, it’s odd to find neither Sander nor those master typologists from the second half of the century, Bernd and Hilla Becher . That is a small complaint, though, against the abundance of striking images on display.

A key point to make about Blossfeldt’s work is that it represents an ideal — that is, a visualization of a nature that is beyond nature. He selected specimens, trimming them as needed, arranging and lighting them just so. The photographs owe as much to his creation as God’s. Artifice was being placed at the service of nature, and the service was anything but subsidiary.

This interplay of the natural and artificial is very wittily, even lusciously, exploited in Lucas Blalock’s pair of color photographs “Strawberries (forever fresh)” and “Strawberries (fresh forever).” Blalock juxtaposes ripe berries with fruit-flavored hard candies in cellophane wrap that resembles strawberries (you know the kind).

The show begins with 42 of Blossfeldt’s photographs in a grid. So arrayed, they could be conceptual art: representation resembling, if not quite embracing, abstraction. Across the gallery, within a single frame, is Doug Bosch’s stunning “Pollen Terrains,” a gridded study of grains of pollen as miniature landscapes. The relationship is obvious between what we see on the facing walls, and plant pollination is the least of it.

The impact of Blossfeldt’s photographs when seen en masse is quite different from when seen individually. The degree of coldness and impersonality and how formalist his approach is are startling. A number of other works share those qualities, such as the set of palms-up hands from Gary Schneider; the 13 photographs of surfaces, ranging from stone to ice to the soles of feet, by Aaron Siskind; or the late David Akiba’s dozen studies of bubbles.

This makes all the more welcome the enlivening presence of Stephen Bridigi’s six views of Pompeii wall paintings or (speaking of series) the wit and imaginativeness of including 16 photographs from Neal Slavin’s “Groups in America.” Presumably, the gentlemen pictured in “Cemetery Workers and Greens Attendants Union Local 365 S.E.I.U. A.F.L.-C.I.O. Ridgewood, N.Y.” would appreciate the association with Blossfeldt’s subjects.

“Truthiness and the News” tackles an immense and vexing subject: the journalistic presentation of information, especially though not exclusively of the visual sort, and the relationship of that presentation to what is factual. If that description sounds a bit vague and all over the map that’s because the show is.

Over here are a dozen or so news photos from the midcentury photojournalist Charles “Teenie” Harris. Nearby is a copy of Rolling Stone, with Richard Avendon’s photo essay “The Family,” about power in America, with a few pages from it displayed. Over there is a video clip of Stephen Colbert’s first use of the word “truthiness,” in 2005. (The term seems almost prelapsarian now.) There’s a set of Sarah Charlesworth’s revisions of front pages of the International Herald Tribune from November 1977. Another set of photographs aren’t examples of photojournalism, we’re told, which is good, because they aren’t; but they relate to events in a way that’s journalistic (huh?).

The whole thing is a bit like a social studies project for bright but easily distracted sophomores. Shrunk down and given a coherent approach — or made several times larger and filled out — this could have been an exhibition to reckon with. Instead it’s a misshapen mess.

Peter Hutchinson, a Provincetown resident, has been practicing his combination of Land Art and photography for more than half a century. Most of “Peter Hutchinson: Landscapes of My Life” consists of large-scale color photographic collages and composites. “Three Continent Mixed Metaphor Mountain Grammar” (now there’s a title with marvelous surfaces, or at least syllables) combines images of the Alps, Rockies, Pyrenees, and Atlas range. “Apple Triangle” shows a yellow wedge made up of the title fruit (are they Golden Delicious?) on a field of basalt. Many of the images are pleasing to look at, and a number of the concepts quite clever. It must be said, though, the loveliness of the deCordova campus at this time of year does rather put the show at a competitive disadvantage visually. Ars longa, vita brevis, yes, but in any contest between art and nature, nature wins.

ALL THE MARVELOUS SURFACES: Photography Since Karl Blossfeldt

TRUTHINESS AND THE NEWS

PETER HUTCHINSON: Landscapes of My Life

At deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, 51 Sandy Pond Road, Lincoln, through March 29. 781-259-8355, decordova.org

Mark Feeney can be reached at [email protected].